67 в

Opening Preparation

Mark Dvoretsky and Artur Yusupov

With contributions from:

Sergei Dolmatov

Yuri Razuvaev

Boris Zlotnik

Aleksei Kosikov

Vladimir Vulfson

Translated by Joint Sugden

В. T. Batsford Ltd, London

First published 1994

© Mark Dvoretsky. Artur Yusupov 1994 Reprinted 1994, 1996 ISBN 0 7134 7509 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Ail rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, by any means, without prior permission of the publisher.

Typeset by John Nunn GM and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wilts for the publishers, В. T. Batsford Ltd, 4 Fitzhardinge Street, London W1H0AH

A BATSFORD CHESS BOOK

Editorial Panel: Mark Dvoretsky, John Nunn, Jon Speclman

General Adviser: Raymond Keene OBE

Commissioning Editor: Graham Burgess

I suggest that you exercise your skill by trying to answer for yourselves the questions which confronted the players in the opening stage of a game played some time ago.

I found this game in the remarkable book Het groot analysebook by Jan Timman, published in 1979. I studied Tunman's analyses with immense interest and to my own great benefit. Certainly, I discovered several mistakes in them. If an annotator doesn’t confine himself to general remarks but makes a genuine attempt to investigate a game deeply, then of course some mistakes are inevitable, owing to the sheer complexity of the problems facing the analyst. Many errors pointed out by readers of the book were corrected in the English edition entitled The Art of Chess Analysis. Then in 1989, Timman presented me with a new edition in French: L’an de I 'analyse.

The commentaries to the games in Timman’s book had been written at various times over a period of years and published in a Dutch chess magazine. The game you are going to sec is one of the first in the collection, and appears to be annotated to a lower standard than the rest. It clearly illustrates the fact that Timman was an indifferent analyst in his youth. Later, with accumulated experience, he began to analyse much better.

You will be given a fairly short time - from 5 to 15 minutes - to find the solution to each of the exercises I set you (some of which defeated Timman himself). But don't worry-you will be helped by some ‘leading questions' which define your task more precisely.

Usually the problems that arc set in competitions have completely clear-cut solutions - such as a forcing combination or a precisely calculated endgame. The test I am about to give you is a little unorthodox. Many questions will be of an obscure nature. It will be sometimes be hard to prove that one line of play is better than another. You will have to trust your general impression of the position, your intuition. Calculation of variations will also be required, of course; but it will be even more important to survey all the resources for both yourself and your opponent, and to assess the resulting situations correctly.

The questions will be of an entirely practical nature, and should be

answered from die point of view of a player rather than an annotator. Your task will be to find - within the limits of the allotted time - the variations which arc most important and most relevant to taking a practical decision. You will need to find the best possible trade-off between calculating variations and making positional judgements.

67 в

Polugaevsky-Mecking

Mar del Plata 1971 Semi-Slav Defence

|

1 |

c4 |

c6 |

|

2 |

£f3 |

d5 |

|

3 |

c3 |

21f6 |

|

4 |

Qc3 |

об |

|

5 |

b3 |

£bd7 |

|

6 |

ДЬ2 |

£d6 |

|

7 |

d4 |

0-0 |

At this point 8 would lead to a well-known position from the Meran Variation (1 d5 d5 2 c4 c6 3 £>f3 £f6 4 £c3 c6 5 e3 £bd7 6 e'c2 £d6 7 b3 0-0 8 ДЬ2) in which White's light-squared bishop is most often developed on e2. However Polugacvsky deviates slightly from the usual set-up.

8 Ad3 3c8

9 Vc2 (67)

Now for the first exercise.

QI Indicate the basic candidate moves or possibilities for Black (10 minutes).

Well, nearly all of you stated

Black's basic ideas correctly. There were even some suggestions that I didn’t have in mind but arc also worth examining. I considered that there were three basic possibilities here:

a) 9...de 10 be c5 - the standard plan in similar positions, provided that the bishop is on c2. With the bishop on d3, it looks weaker.

b) The immediate 9...e5 - in such cases you always have to decide whether it pays to allow an exchange on d5.

c) The preparatory move 9..№eT, the idea of which will be discussed presently.

Vadim Zviagintsev suggested the totally different plan of completing Black’s development with ...b6 and ...Ab7. I shall not discuss this suggestion at any length, as I have not analysed it, but it seems quite sensible, and Black does sometimes play that way in similar situations - so it scores a bonus point.

Let me now state my own preference. The move I like best is 9...‘tt'e7. Of course I cannot prove anything

I can only offer an explanation. What is the idea of the move? Well, let us consider - why didn’t White castle on move 9? Because of the reply 9...e51. White would then be unable to take on d5 in view of the fork with 10...e4. He would have to exchange on e5 in circumstances favourable to Black.

The point of 9 ‘«'c2 was to keep control of the e4 square, so that after 9...c5 White would have the chance to exchange on d5. This explains Black’s quite subtle reply 9...fi’e7. It is a useful move in this kind of position anyway, but in addition Black renews the threat of the fork after ...еб-е5.

Vasya Emelin was the only one to choose this move - for this I award a bonus point to him too.

9...'й'с7 was not played in the game or indicated in the notes. It is essentially an opening novelty, and quite a good one. This indeed is how novelties arc devised; you just have to investigate the game or opening variation attentively and fathom its concealed ideas.

In his list of ‘candidate moves’, Yan Teplitsky gave almost every feasible move including 9...c5. This is rather overdoing things; it is like trying to fire a broadside. With such an abundance of possibilities, it is hard to reach any precise conclusions; too much time is needed. Try to use your judgement to set some limit to the list of candidate moves.

9 ... e5

10 cd cd

In such positions the typical move £jb5 is sometimes played, but of course not here in view of the check on b4.

11 de ®xe5

12 4ke5 Дхе5

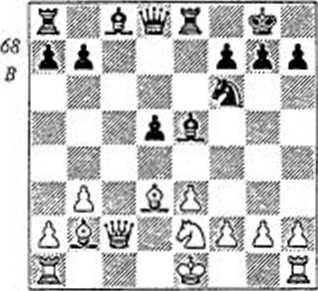

13 $>2 (68)

The last few moves by both sides were fairly logical. White is trying to simplify the position by exchanging the dark-squared bishops. Now Black has to take a crucial decision.

Q2 How should Black continue? (10 minutes).

Given quiet play. White will obtain a small but stable positional advantage. So above all you should look at moves which disrupt the ‘normal’ flow of the game.

The first attempt is 13...’efa5+ 14 ДсЗ Axc3+ 15 Wxc3 Vxc3+ 16 ФхсЗ, and now 16...d4 - since otherwise White would have the more pleasant ending. After 17 4iJb5! Black must sacrifice the exchange with 17...de 18 *£k7 ef+.

You nearly all reached this position in your analysis, but not everyone succeeded in following the variation through clearly to its end. However, in the first edition of his book, even Timman went wrong. He gave an exclamation mark to the bad move 19 sfcd2?, which is refuted by I9...2d8 20 Cixa8 £f5. The right continuation, of course, is 19 ФхГ2 £g4+ 20 *gl Sd8 21 £xa8 2xd3 22 h3. An almost identical position -imagine the black rook on d2! -might be unclear owing to the bad position of the white king. But as it is, White has everything in order, for example 22...4У6 23 ФЬ2, or 22...£jc3 23 ФГ2. Black doesn't have proper compensation for the exchange.

This whole variation occurred in a later game. Makarychev-Chckhov, Moscow 1981.

Seeing that the exchange sacrifice is unsound, the check on a5 has little point. Another active try is more interesting- 13...d4!?.

If White replies 14 f4 or 14 2d I, then 14...tfa5+ is strong. In answer to 14 cd, one of you suggested 14..JLd61?. After 15 0-0 Black has a bishop sacrifice on h2. After 15 h3. Black has 15...'«ra5+ 16 ЛсЗ <h5 or I6...#g5, exerting pressure on the kingside. Very clever! The simple 14...^xd4 is also quite sufficient for equality.

The thematic reply is 14 c4! (69). This is crucial for the evaluation of ...d5-d4.

69 8

Q3 What are the consequences of 14...Фхе4 ? (5 minutes).

You all without exception gave the correct verdict. After 15 Дхс4 d3 16 ^xd3 ДхЬ2, White should not play the move given by Tirnman -17 2d I?'^05+-but simply 17 Axh7+! ФЪ8 18 «ЪЬ2, and Black has no compensation for the pawn sacrificed.

What should Black do instead, then? White has the belter pawn structure and is threatening to advance with f2-f4. The ending after 14...W,a5+ 15 Wd2 is clearly in his favour. Black must act as energetically as he can, and I think the only serious possibility is 14...£}g4!. But after 15 h3, what is the reply? Black can deprive his opponent of castling rights, but after 15...'й,а5+ 16 ФП the advantage is still with White. A stronger move is 15...Wh4. Now after 16 0-0, Black can strike with 16...Qh2!, and all kinds of threats arise: ..JLxh3, or ...®f3+. It is true that by playing 16 g3. White suddenly reminds his opponent that the d-pawn has been en prise for some time. But Black is not disheartened, since after 16..Ж6 17 £)xd4 Ш or 17...Sd8, the situation on the board is as cortfused as ever. Can you by any chance give a verdict on the final position of this variation? I worked out this whole series of moves in my analysis, sifting and discarding the alternative lines. Black is clearly justified in playing this way. It is risky for him - he remains a pawn down - but White too is taking a risk with his weakened kingside and his king stuck in the centre.

So the conclusion is that Black has the queen check on a5 which is not very effective, and also the enticing 13...d4:? which attempts to stir up complications. But Mocking opted for a different move:

13 ... Wd6

To assess this move objectively, you need to do the following exercise.

Q4 Annotate the next series of moves played in the game (15 minutes).

14 Дхе5 Wxe5

15 0-0 £d7

16 £d4 (70)

First let us evaluate the diagram position. It is evident that after the exchange of dark-squared bishops, White retained a slight positional plus due to his opponent’s isolated d-pawn and passive light-squared

70 В

bishop. It is not certain that White will be able to win, but at any rate he will be pressing throughout the game. Could Black have avoided this prospect?

Some of you suggested taking on c5 with the rook instead of the queen. I shall not give any points for Chis, for I don’t see any particular merit in it. White replies to 14...Kxe5 with 15 £kl4, and is not worried about 15...M4+ 16 Wd2Wxd4?? 17 Axh7+. He plans Hcl, followed (if he has the chance) by 'fife?. It is also worth considering 15 Scl d4 16 c4.

After 14...Wxe5 15 0-0, the recommendation of 15...^4 is unconvincing. White puts his knight on d4 and at a suitable moment can even exchange on c4, emerging with a strong knight against a passive bishop. Black’s position has the same defects as in the actual game.

However, the move 15...£)g4! gives Black quite good counter-chances; it enables him to stir the position up. Naturally you could not work out the variations accurately in the short lime, but your positional judgement rightly tcld many of you that this was the move Black had to decide on. The logic that operates here is typical of such situations: before resigning yourself to defending passively for the whole game, you must first look for any active resources that may change the unfavourable course of events. ?\nd if a move such as 15...€lg4 has no direct refutation and leads to unclear situations, it should be played.

But White, for his part, could also have played more strongly and not allowed this unnecessary sharpening of the fight. In place of 15 0-0, a good method was 15 й'сЗ!. Many of you pointed it out. It is important to drive the black queen off its excellent central square. The position after 15...'«6x3+ 16 £jxc3 is one that we know already from the variation 13...'®'a5+; our analysis of it was net superfluous. As you recall, !6...d4 17 <lb5 gives White die advantage; while if the black queen retreats, White can castle or play 16 #d4.

Would you suggest answering 15 w’c3 with 15...Wg5.„? Well, While simply castles, and 16...JLh3 is harmless because of 17 Sif4. White plans O’d4 followed by ’ST4, or the even more active Wc7. At any rate, in this line there is none of the counterplay which flares up after 15 0-0?! £ig4!.

Volodya Baklan indicated the variation 15 'Й'сЗ 'ЙЪ5 16 0-0 £3g4 17 h3 ■tieS. But after 18 •$jf4 White still stands a little better; the pawn on d5 is weak. White is net obliged to castle but can play 16 '«'d4. Still, on the whole it is true that Black has to wriggle somehow. I award a bonus point for this attempt to work out the consequences of 15 #c3.

We arc now in a position to assess 13...’8'd6 objectively. It leads to a somewhat inferior, passive position. Black should have preferred the more dynamic 13...d4!?.

I give the maximum score of ten to those who pointed out the counterattacking idea 15...£lg4! for Black as well as the move 15 ’й'сЗ! for White. In two cases, your answer was based on the correct assumption - White has to think up something in place of 15 0-0, in view of the strong retort 15...^jg4! - but the move you gave was not ‘»’c3. For this 1 awarded part-scores between five and ten. Yan Tcplitsky scored the least points because he ‘fired a broadside’ just as in the first exercise. He had been warned! Once again he pointed to a mass of possibilities including the correct ones, but didn't give a clear preference to any of them. You shouldn't be afraid of expressing your opinion. Of course it may turn out to be mistaken, but you learn from your mistakes. After all, the true aim is not to score maximum points in this competition. We are trying to develop an approach to decision-making, which you can utilise in practical play. In practice, you are obliged in the end to make a clear-cut choice between a move you like less and one you like more.

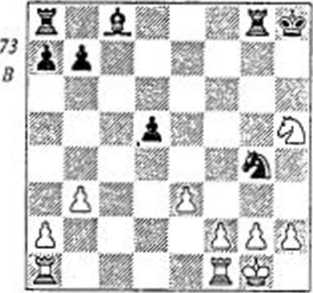

Now lei us take a Giorough look at the variation 15 0-0 ^)g4!. How docs White defend against the mate? The first attempt is 16 g3 'ЙЪ5 17 h.4 (71).

71 В

ill ИАИА

йдшш о

Д|*1Ш Й

Q5 How should Black continue? (5 minutes).

Here Black has the powerful move 17...g51, which gives him a splendid position and a strong attack. The threats arc ...gh, and if appropriate ...Фе5. You analysed 18 ■d?g2. The reply I had in mind was 18...gh 19 Eh 1 h3+. In one of die answers. someone wrote that 18...gh was a bad move because of 19 $3f4.1 don’t think so - after 19...h3+ 20 ФЫ #h6, Black stands well. But perhaps 18...Zxe3 is even stronger. The student who suggested this scores a bonus point.

The only difficulty about this exercise is die fact that Black has another tempting move, 17...&c5, which is not so easy to reject This was actually the move recommended by Timman, but if we continue the variation with 18 53f4 $3f3+ 19 Ф$2 '^g4 (the piece sacrifice 19...5ixh4+ 20 gh ^4+21 St?h2 'Й'хЬ4+ 22 Ф-g 1 ’Я^4+ 23 £)g2 is also inadequate) 20 Ehl. then it becomes clear that with White’s very unpleasant threat of 21 Де2. the position must be assessed in his favour.

Let us continue our review of the defences to the mate threat which arises after 15 0-0 £>g4. The second try is 16 £g3. In this case there are scarcely any questions to be asked; Black obviously replies 16...h5l. Play continues (let us say) with 17 Efel h4 18 Qfl h3 19 g3 Ш, followed by ...£c5. An attack on the light squares commences; Black’s position is clearly better.

Timman recommends 16 ■S)f4, and comes to an amusing conclusion: after 16...£)f6 (with a view to 17...d4) 17 Фс2 &g4 18 <&f4, the game ends in a draw. But docs Black need to bring his knight back? He has two active moves, 16...g5 and I6...d4. In the first edition of his book (in Dutch), Timman wrote that both these moves were bad. In the English edition he only rejected one of them. It was not until the French edition (which took into account an article of mine published in New in Chess, criticising the mistakes in his book) that he gave the correct verdict - both moves promise Black an excellent game.

I will demonstrate one of these variations now. I shall then ask you to work out the other.

I6...g5 17h3gf! 18e№f4 19 hg jLxg4 gives Black the advantage. If White regains his pawn by taking on h7, Biack will attack in the h-tilc. Where did Timman go wrong here? He was led astray by the attempt to win a pawn: 17...£)xc3? IS fc 'ЙгхсЗ+ 19 ФЬ2 gf 20 Sf3, and by new it is White who is mounting a formidable attack.

The second variation begins with 16...d4 17 JLxh7+sth8 18 h3 (72).

72 в

Q6 What position should Black be aiming for? (10 minutes).

Black has quite a few tempting possibilities. There arc some fairly sharp, complicated lines; you cannot of course analyse them fully in the space of ten minutes. The aim is not so much to calculate as to estimate, to acquire a feel for where your advantage lies and what kind of position will be soundest. Try it.

Timman examines three continuations. The first goes I8...$3xf2 19 Wxf2 de 20 Ш g5 21 'йЪб tig! 22 >xg7+ £xg7 23 £)h5+ <£xh7 24 <2)f6+, and White wins. The second goes 18...€)f6 19 &g61! (the pawn on f7 is awkward to defend) 19...de 20 £xf7 Orxf4 21 ДхеЗ £xc8. Black has gained two pieces for a rook, but his game is untenable owing to his weak king position; after 22 fc! ^xe3+ 23 $hl, While’s threats arc irresistible. Finally, the third continuation goes 18...de 19 hg cf+ 20 tt’xf2! ФхЬ7 21 Sack But why should Black commit hara-kiri, opening up lines for his opponent's rooks? In this last line he has the perfectly simple 19...Wxf4! (instead of 19...ef+?), giving him splendid prospects.

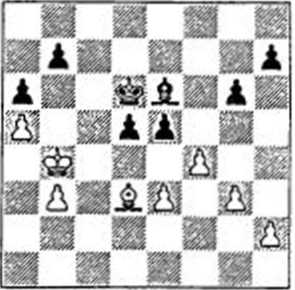

So we see that after 16 5)f4 Black is by no means compelled to settle for a draw but can choose between two attractive possibilities. What is White to do, then? Did his imprecise move 15 0-0?! really give him the worse position? I do not think so. There is one more variation to examine: 16 ^xh7+ Ф118, and only now 17 £lg3. Obviously Black ought to win the bishop for three pawns: 17...g6 18 JLxg6 fg 19 'fi'xgb, with the probable continuation 19...Sg8 20’&Ъ5+ tfxh5 21£xh5 (73).

Solving endgame studies is one thing. Once you arc lucky enough to hit on the right sequence of moves, it is generally no trouble to evaluate the end position - it is a straight win, draw er loss. Practical play is much more complicated. Here, forced variations very often culminate in wholly unclear situations. I do not

know what judgement to pass on the diagram position. If anyone docs know, let them tel! us! But in any event I maintain that this is White’s best option in response to the knight sortie 15...£jg4’.

If Black had played that move, imagine how hard White's task would have been! He would have had to examine 16 £jg3, 16 £if4 and 16g3-and then select this piece sacrifice (16 Axh7+) by process of elimination. He would have needed to feel - since exhaustive calculation was impossible - that everything else was dangerous for him. whereas in this case an unclear ending would arise.

We have now finished with the opening stage of the game under discussion. The play settled down to a quiet middlegame. It would be wrong to assert that White had a large plus, let alone a won position. Experienced, cool defenders arc usually capable of saving themselves in-this kind of situation.

But subsequently the difference in class between the two opponents made itself felt. Polugaevsky is a mature positional player. As for Mecking ... A year after this game, Tigran Petrosian wrote about him: 'Certainly, he is by no means a bad player. Perhaps he will improve, but I am convinced he will never be World Champion. This is mainly because of the narrowness of his chess thinking. For example, Mecking does not understand the significance of weak and strong squares. I have played him three times. In 1968 he lost to me owing to the weakness of his light squares. A year later he presented me with all the dark squares and again suffered defeat. And in the San Antonio tournament of 1972, Grandmaster Mecking again let me have dark-square control. and with it - victory. What distinguishes Mecking is lively piece play, but he has no genuine grasp of the underlying nature of a position; this is what makes me have doubts about his future as a player.’

A severe but instructive ‘diagnosis’. I would point out that a weakness on squares of a particular colour usually results from placing pawns on the same colour of squares as your bishop. Wc shall see Mecking commit precisely this elementary positional error.

Here is how the game continued.

16 ... Sac8

17 Be2 ^d6

18 Wb2

Take note: if you have a light-squared bishop, it usually pays to place your queen on a square of the opposite colour. White covers the vulnerable squares on the queenside, and prepares to advance his pawns there if the occasion arises.

18 ... аб?!

Petrosian is proved right - Mecking doesn't know which squares to keep his pawns on.

19 Eacl £g4

Too late! This no longer has much point.

20 £f3 Wb6

21 S.xc8 2xc8

22 Scl

Polugaevsky follows the well-known rule: ‘Take young players into the endgame'.' It is easy to sec that 22...®xe3? fails to 23 Sxc8+ Дхс8 24 #cl or 24 ^e5.

22 £f6

23 Hxc8+ Дхс8

24 'й'сЗ Д47

25 £44 Фе8

26 a4!(74)

74 в

There is an old saying: ‘When two do the same thing, it is not the same.’ Polugaevsky places a pawn on the same colour square as his bishop, just as Mecking did before. But his aim is to advance it further, to fix his opponent’s quccnside. If Black plays 26...a5 to thwart this plan, there follows 27 Ab5! Axb5 28 &xb5. This kind of device - which incidentally is quite difficult, and demands a subtle appraisal of the position - is called the transformation of advantages. White gives up one of his trumps - he exchanges his opponent’s ‘bad’ bishop - but in return he procures another: a clear superiority in the placing of his pieces. Black will have great difficulty defending the entry points.

26 ... &c7

27 Vxc7 £xc7

28 aS

Here it was essential for Black to work out 28...£te6!?. If 29 £Jxe6, then 29...fe 30 f4 &П, followed by ...h6, ...ФГ6 and ...e5. This was his best chance, giving realistic hopes of a draw. But Black plays a superficial move instead.

28 ... ФГ8?!

29 ФП

Now the idea no longer works -after 29...£jc6 30 £}хеб fc?, the pawn on h7 is en prise. But Black could have played 29...h6 and only then ...£k6.

29 ... Фе7

30 Фе2 g6

Funny to see a grandmaster play like this! He sees that 30...^кб is met by 31 Qf5+, and without any hesitation places one more pawn on the same colour squares as his bishop.

31 Фаз £кб

32 £>хс6?!

I find this hard to understand. The obvious move was 32 ФсЗ.

32 _ fc

33 f4 c5

34 g3 Фаб

At this point Timman tries to show by detailed analysis that Black could have held out with 34...ДЬ5!. To me his variations don’t seem sufficiently convincing, but there is no doubt that this was Black’s best chance. At any rate. White could not have gone into a king and pawn endgame, since after 35 ДхЬ5 ab 36 ФсЗ Феб.1, Black can answer 37 ФЬ4 with 37...d4!.

35 ФсЗ

Now 35...ДЬ5 is no longer playable; in the variation 36 ДхЬ5 ab 37 ФЬ4 d4, White captures on c5 with check.

35 ... Дсб

36 ФЬ4 (75)

We now come to our final exercise.

Q7 What would you play here? (5 minutes).

Mocking has spoilt his position enough already, and I am not convinced it can be held. But in any situation you must fight.

White threatens to play 37 fc+ Фхс5 38 Фс5, penetrating on die dark squares. If Black exchanges on f4, the white king will transfer itself to d4. It is unlikely that White would fail to exploit such a huge positional plus, with all Black's pawns on the same colour squares as his bishop.

The most natural move is 36...d4! (if only to put a pawn on a dark square). I only gave you five minutes because it is not necessary to calculate the move exactly. A cursory appraisal of each side’s resources is sufficient. Perhaps this move loses all the same, but it is not such a simple matter. White would have to come to a decision - to take on d4 or c5, or perhaps play 37 c4. But who knows which of these is correct?

Timman, at any rate, docs not know. At first, for some reason, he didn’t examine this defence at all. After I had pointed it out in my article, he wrote in the French edition of his book that White wins with 37 c4, followed by 38 fc+ Фхе5 39 Фс5 ДхЬЗ 40 ФЬ6. Nonsense! Black has nothing to fear after 40...Д41 41 ФхЬ7 Д f3. In any case, if he wishes, he can easily parry White’s ‘threat’ with 37...Ad7.

36 ... cf?

This further confirms Petrosian’s remarks about Meeting's poor positional understanding. The remainder of the game is a lucid illustration of how to win such endings.

37 gf Ag4

38 ФсЗ ДО

38...Фс5 39 Ь4+.

39 Фд4 £g2

If White had the chance place his bishop on the hl-aS diagonal, he could break with c3-c4 and attack the pawn on b7.

40 h4 ДГЗ

41 b4

Before starting the decisive action, White makes all the useful moves to improve his position - following the well-known endgame rule, ’Do not hurry!’

Incidentally, this statement is not as obvious as you may think. Arc these pawn moves really useful to White? After all, a zugzwang position might well arise, where a tempo move with a pawn (Ь3-Ь4 or h2-h4) would be very handy. It is likely that Polugacvsky already sees how he will break through; he knows he dees not need to keep any tempi in hand for the purpose of giving his opponent the move.

|

41 ... |

ДЫ |

|

42 Де2 |

Ag2 |

|

43 Дg4 |

Дс4 |

|

44 Дс8 |

Фс7 |

|

45 Деб |

Фd6 |

|

46 Дб8 |

Ь6 |

|

47 ДС7 |

Ь5 |

Forced.

50 fS!

This break overthrows Black's defence. If 50...gf, then 51 ДхЬ5 and the passed h-pawn is decisive.

The final moves were: 5О...Дх15 51 Ji.xd5 ДсЗ 52 e4 Фе7 53 Фе5 g5 54 hg h4 55 g6 h3 56 g7 h2 57 g8» hl» 58 »Г7+ Фа8 59 Wf8+ 1-0

Let us think about the reasons for Black's defeat. As regards the middlegame and endgame, everything is clear. Enough has already been said about Meeting’s failure to understand the simple positional question of which squares to place the pawns on.

But then, the seeds of defeat were already sown in the opening or in the transition from opening to middlegame, when Black was left with an unpromising position. Why did that happen?

Meeting played very passively, conceding the initiative to his opponent. He didn’t utilise the attacking opportunities that presented themselves in the opening - 13...d4! and 15...£g4! (or for that matter in the endgame - 36...d4|). Perhaps this was because he didn't sense the strategic danger in the situation. Mecking may have imagined that defending against an experienced grandmaster is simplest in a quiet position. But this is a fundamental error. The very thing an experienced grandmaster wants is to play a position in which he is risking nothing and the only question is whether he is going to win or draw. A double-edged game with a risk of losing is far less congenial to him.

It cannot be said that White's opening play was ideal. By failing to find 15 'й’сЗ!, he gave Black the chance for 15...£>g4!, which would have abruptly altered the character of the fight. But afterwards Poluga-evsky's conduct of the gxme was entirely rational.

Passive tactics in the opening stage are dubious. What is needed is the opposite - maximum energy as well as maximum precision. After all, the outcome of the opening skirmish frequently determines the whole complexion of the subsequent play. The basic theme of these exercises was nothing other than the struggle for the initiative in the opening. You were training yourselves to find concrete solutions to opening problems.

Now for the results of our competition. The top scorers were bunched together. The single point difference between the winner and those who shared second to fourth places was of no great significance. The contest did nonetheless have an outright winner, and it was Maxim Boguslavsky with 38 points. I congratulate him:

The next three places were shared between Dragiev, Emelin and Geor-giev with 37. .Makariev and Zviagintsev scored 35 points each. Makariev fell down rather badly at the start, in his analysis of !3...#a5+. Vadim Zviagintsev failed to cope with the series of moves that had to be annotated; he didn't indicate 15...<£g4! -a very serious omission. /\part from this major failure, he did well in all the exercises. Volodya Baklan gained 33 points. The lowest score on this occasion went to Yan Tcplit-sky. You see how hard it is when you join in competitions at the last moment. He had only just arrived and evidently didn't have time to acclimatise himself.